I think I was probably well into my adolescence before I understood that the word "pregnant" could actually be spoken above a stage whisper.

When I was eighteen and groping my way blindly through the minefield of college sexuality, "pregnant" was one of the scariest words in my vocabulary. When I was twenty-four and at my first real baby shower, traumatized by the balloons and the sorority-style squealing and those bizarre paper hats, "pregnant" felt like a word from some foreign language I couldn't fathom being fluent in. When I was twenty-nine and in the midst of a divorce and a PCOS diagnosis, "pregnant" began to feel like a heartbreaking word, one that might slip through my fingers forever. When I was thirty-two and the pee stick turned shockingly positive for the first time, "pregnant" became a magical incantation that I whispered to myself, secretly, almost in disbelief that such wonder had ever come to pass.

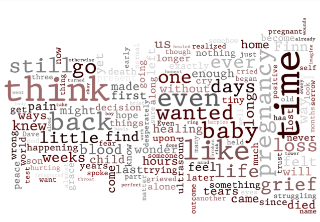

It was the next spring, at thirty-three and deep in the bone-numb grief of mourning my firstborn, that I lived all those incarnations of the word - the shameful and horrifying and foreign and heart-searing and secretly longed-for - all together, each time I encountered a ripe belly. They echoed all the long weeks up to my due date: that could/would/should have been me. Bellies seemed to sprout up everywhere, the world a sudden minefield of them. And each one, beautiful and poignant, full of possibility, made me gasp for breath and sent my shoulders hurtling up over my ears and my eyes skittering to the street. To a babylost mother, there's little so evocative, so exposing and so wrenching as a healthily glowing pregnant woman, the Other, our opposite, blithely traipsing down a path that has dumped us remorselessly overboard and marked us Not Wanted On the Voyage.

Which makes the whole conversation about pregnancy after loss a little awkward, and being pregnant, in the company of fellow Medusas, a little like being the elephant in the proverbial room.

I am twenty weeks pregnant today...a round, portentious number in a body becoming more round and portent by the day. I am on bedrest, that strange half-life, existing and interacting mostly online. I am disembodied, in a sense, and perversely grateful for the cloak of this purdah, this enforced hiding from the world. Because in being pregnant, I already embody enough of my own nightmares that I'd just as soon not trigger anyone else's while they're innocently out for groceries. And yet here, in this good company, I know my words have just the same power to wound as my silhouette would if you ran across me in the checkout...that in owning the elephant, I risk sending someone's eyes darting away from the screen, hot with tears; I tread on scars and the plaintive sorrow of why not me?

I don't want to, but I do, just in being here. I know that, and I am sorry.

I know I am profoundly lucky that pregnancy after has come easily, or at least conception has. I had my second son, then a nine-week miscarriage, then a positive pregnancy test that's brought us safe thus far to this midwayish point, all tenterhooks and cervical stitch and quivering, half-naked hope I can still barely look in the eye. But it is in the hope where the luck resides: hope spins futures, however cobwebby. And it is futures, dreamed and cast to ruin, that haunt those who mourn.

In the early weeks after Finn died, when I was still waking shocked to find my body empty and no longer pregnant, I wanted desperately to turn back the clock. I felt wrong, robbed. I wanted to be pregnant, to rectify this hole that had somehow ripped its way through the space-time continuum. As acceptance began to beat its way into me, and I flailed like a fish on a line trying not to confront the weight of my grief head-on, I wanted again to be pregnant...to force the hand of fate and try to peek, somehow, into a future I could no longer imagine. But these were not the clinchers, not the reasons that led me to throw caution and the pill back to the wind. It was more a compulsion than a decision, ultimately...an inarticulate, animal pull, like a cat in heat. I felt reckless. I wanted to breed, to be fecund, to ripen, to throw myself at pregnancy with all the fierceness I could muster. I wanted to make babies, hundreds of babies. I wanted it like I have wanted nothing else in my life, like it was the brass ring, the hope that would bring back hope.

And yet when I locked myself in my bathroom to take that home pregnancy test, five months after the death of my baby, I didn't feel hope. I felt ridiculous, exposed, foolish. I imagined cackling harpies crowding at the door, taunting me: look at the crazy lady whose baby died, conjuring up pregnancy symptoms! pitiful! nutjob! bwaa haa haa haa! Even when the test turned positive, they didn't have the decency to disappear, those harpies...they just altered their tune a bit, drowning out any hope I summoned, reminding me that I had no reason to expect that all would go well.

I did not trust my body. I did not trust my instincts. I once again had something precious to lose, to fear losing, and oh, how I feared with all my heart. I became fixated on dates, on counting, on parsing out days until the heartbeat, the ultrasound, the window for x to go wrong, the next ultrasound, viability, the gestational age at which Finn died.

I still do it. For a brief window last fall, I had the most uncomplicated few weeks of pregnancy I've ever known. Even with Finn, I'd begun bleeding a few days after I found out I was pregnant, and had thought for a week or more that I was miscarrying. With my second son, I bled from the day of the positive test, harpies bleating, and died a little each time I peed for the entire seven months after. So when my pregnancy last fall hit the six, seven, eight weeks with no sign of blood, I began to strut a little, inside, began to race ahead of myself with hopes and fantasies...began to think, this is what it feels like to be normal. I felt the strange conviction that all would go well. Ah, hubris. The nine-week ultrasound showed that the fetus had never made it past six weeks.

So this time too, again, I leapt in still bruised, still with healing yet to do. I leapt in acutely aware that what I want and what I think mean squat, in terms of outcomes of this pregnancy, understanding that if we were lucky enough to get out of the first trimester there would be bedrest, possible medical complications, all these things that scare the living shit out of me. I still forgot that for days before every ultrasound I would manage to convince myself, subconsciously, that the baby had died...and thus leave with good news but feeling worse, as if the inevitable torture had merely been postponed. I still forgot that the societal discourse surrounding pregnancy - all bloom and celebration and oooh, fight stretch marks! and let's have a shower at twenty weeks! and if something were wrong, mama would know - would make me feel like drinking rat poison...or like feeding it to the oblivious smiling hordes, so certain in their entitlement, their claim to a "rewarding" pregnancy. I still forgot that I would choke on the words, "I'm pregnant," just as if I were an adolescent or a frightened eighteen year old...that I would feel sheer terror at the prospect of having to expose that much of my secret soul - my fragile hope - to people even long after my body was negating the need for an announcement.

What I did not forget is that it is a gift, this one more try.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

What is your relationship to pregnancy after? Is it a possibility? Something longed for? Feared? If you've had multiple losses, did you find your relationship to the subsequent pregnancies different? Did you choose an alternative path to having further children?

If you have been pregnant after loss, what was the experience like for you?

And lastly...is this a topic you're comfortable encountering here, and if so, under what circumstances and terms?