gone is the ultimate goal

/In July 2006, Rosepetal’s first son V was stillborn at full term—one day before her scheduled induction and three days after a check-up with heart rate monitoring and ultrasound showing that all was well. She discovered the world of baby loss blogs shortly afterwards and began her own—Moksha—and joins us for Glow's Are You There, God? It's Me, Medusa blogolympics.

Although Rosepetal’s family is Hindu, she was not brought up in a particularly spiritual way. There were no daily prayers within her household, no shrine in a corner of her childhood home and, at the time, no local Hindu temple in her hometown.

"I spent a lot of my childhood rejecting all things Indian, not being interested in Hinduism and just trying not to be different," she explains. "I have no spiritual leader, and patchy beliefs and understanding. When I was approached by Glow in the Woods to write a piece, I felt a little bit fraudulent being put forth as a Hindu voice. But this gathering is all about context and not credentials, and so here I am."

Rosepetal was born to Indian immigrants in 1973 in England, and lives now wih her husband and living son in Europe.

It is in our hands to plan and do everything to the best of our capabilities but the results are in the hands of God. The way in which every living being comes to earth depends on accumulated karma. The better our deeds, the better the opportunities we get in this life to perform better deeds. In the end some pious souls get freed from this cycle of rebirth.

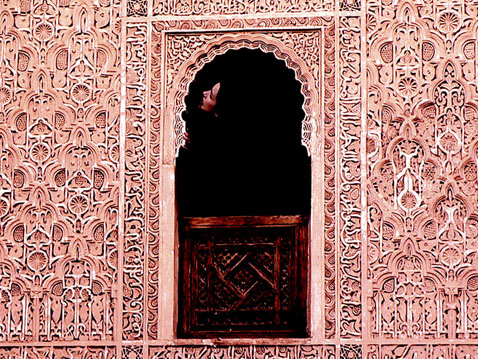

I believe that your young son was one such Divine Soul who only needed a short time before being freed forever from this cycle and will now become one with God. It is called moksha, the salvation. You [and your husband] were both the chosen ones for this to happen.

So wrote my cousin in India after the unexplained death of my son at full term.

Comfort was in very short supply and this was one of the only letters I found comforting at the time. It presented V as having his own thing to do, his own destiny, one which I could not—and maybe even should not—have prevented.

There are two main views on what moksha, the ultimate goal for Hindus, is like. One states that the soul retains its own identity upon attaining moksha and continues to exisit in an enlightened state of perfection. The other states that the soul loses all individuality and becomes at one with the whole—you might call the whole God—and is indistinguishable from it. A useful analogy is that it is like an individual drop of water falling and merging into the ocean. It is the latter which I believe makes most sense.

When my father died suddenly less than a year after V's death, I sobbed to a friend that I must have done something really awful in a previous life. But the truth is I don't really understand how the paths of different souls intersect in this way. How come V attained moksha and I became the mother of a dead child?

Today I find the idea that V attained moksha both comforting and distressing. Comforting because that is the ultimate goal for any soul. Distressing because it means he no longer has any attachments to me and no longer even exists as individual entity. Whereas once I felt sure that I would find him again after death, that the mother-child bond was that strong, now I fear that it is in fact impossible. Maybe that explains why these days I feel so very far away from him.

But there is a small beginning of a grain of understanding of what it must take to attain moksha. As I cling to my individual self, I see that I am nowhere near.