Why are we here? All of us, I mean, humanity? Philosophers have been at this for millennia. So have uncounted and uncountable others. What we call regular people. Happy, unhappy, kind, lonely, content, brilliant, sad, successful, lovely, mean-- all kinds of people.

I found my answer long ago. I would like to say that I found it in my freshman biology class, but I would probably be lying. I certainly met the concept there, but it wasn't until a few years later, when my work in the lab required me to consider its moving parts, or maybe not even fully until I started teaching, that the idea blossomed and made itself a home right in the center of my brain. It wasn't a particularly painful process, as major mental model reconstruction projects sometimes tend to be-- I must've been ready for it, ready for this unifying idea to bring together life and science. And even still I find this understanding, this answer to be both astonishingly simple and just a little bit subversive. Not in the sense that it challenges rules and order, but in the sense that it comes back to shift the question itself.

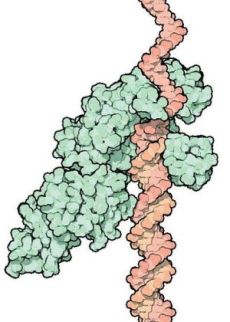

This. This sea green thing is my answer. A molecule, or, rather, a type of molecule. DNA Polymerase-- an enzyme, an incredible, precise machine, modeled here hard at work. What DNA Polymerase does is replicate (copy) DNA (there is a bunch of related molecules in the cell performing various components of this function, from straight up copying, to fixing particular types of errors that occur due to impact of specific elements of the environment, like for example UV rays from the sun; but since they all share the central feature I am talking about, I am going to talk about it here as if it's all one molecule). In the picture, DNA is the tightly wound thing in coral tones. In reality, it's the sourse of heritable information in the cell. In (almost) every cell in our bodies. In every living organism on Earth. (Viruses don't count-- they are not technically alive, since they need a host to proliferate. Viruses carry their genetic information either in DNA or in RNA, a closely related and most likely older molecule.)

To make a new cell, whether to grow and develop, heal a wound, or create a gamete for procreation, we need to replicate our DNA. Cells, you see, come from other cells. And the way they do it, roughly, is to copy DNA, segreagate it evenly to the future daughter cells, and pinch off the membrane in the middle to make two from one.

DNA is a double stranded molecule. But the beauty is that the information on how to make each strand is stored right in its partner strand. So if you separate the two (and there are enzymes to do that part as well), you can create two copies of the original by following the instructions in each of the single strands. Which is what DNA Polymerase, that sea green thing in the figure, is doing. You can see the single strand being single in brighter pinkish tones towards the top of the figure, continuing in the same color towards the bottom. But you can also see the new strand that the polymerase is making in duller orangish tones below the position where the polymerase is holding onto the strand the closest.

One last bit of science before I get to my point. The information on how to make the new strand is stored in the old strand very locally-- for each position polymerase is to fill in, the information on what piece needs to be put in is stored right across, in the corresponding postion on the old strand. This means that if it accidentally inserts a wrong piece, it should be able to sense it, delete it (via a different part of the molecule than the one that puts the pieces in), and try again. This is one of the mechanisms that makes the machine so accurate.

So here's the thing. DNA Polymerase is very very very accurate. Mindblowingly accurate. But it does make mistakes. Like once in a blue moon. But, our genome is about one third of a blue moon long. So it makes a mistake about every other time a cell's genome is replicated (because it makes two copies every time it replicates one cell's genome-- a new strand for each of the old strands).

These mistakes are not necessarily bad things. Sure, some of them cause cancer and other diseases, and some cause miscarriage. But a lot of them are entirely harmless, occuring in a region that doesn't seem to have a function, or changing only the way the instruction is written in the DNA, and not the instruction itself. And some of them are actually beneficial.

In fact, my answer to that first question, the reason we are here at all is "because of that very low rate of errors of DNA Polymerase."

For example, a long time ago there was no oxygen in Earth's atmosphere. Mostly sulfur. So first, due to some of these errors (and maybe other genome-changing variations, such as copy/paste of whole sections), some bacteria developed a system to use the energy from the sun to change carbon into the form that can be used for growth, using a sulfur compound to make the system go. Later, another bunch of copying errors allowed some bacteria to start using water instead of the sulfur compound in that system. That process produced oxygen. And since water was even more abundant than the sulfur compound, slowly, very slowly, the oxygen-making organisms occupied more and more space, making more and more oxygen, eventually changing our atmosphere into what it is today.

Many-many other changes occurred through the billions of years Earth has been around, both before and after the events I described above. Diversity of organisms populating the planet today, diversity within organisms, difference in the types of organisms living in one type of environment versus the other-- ultimately all of this is down to DNA Polymerase making those very few mistakes every couple of blue moons. If it wasn't for it making mistakes, there would be no humanity. To be fair, there might not even have been yeast. But very definitely no humanity.

And this is where I jump to the dead baby thing. Because while some of these errors allow new traits and whole new species to emerge, some of them cause miscarriage. Some of them cause birth defects, some extremely challenging and some fatal. This is why I am so very comfortable saying that there is no reason for why my baby died. It was random, shitty piece of luck. I don't know whether the particular things ruled to be the cause of his death were due to the actions of DNA Polymerase, some other part of cellular machinery, or environment interacting with otherwise ok parts of his or my biology that caused it, and in this sense it doesn't matter to me.

This is why I never ask "why us?" The scientific answer to "why us?" is, I know, "because of random events that occurred sometime during gamete production, fertilization, implantation, or development." The answer to "why me?" (if someone asks me to differentiate that from the "why us?" question) is "because he died, and I am his mother."

My philosophical/religious answer is also grounded in this scientific reality. "Why not us?" is that answer. Why should we be exempt from the luck of genetic, developmental, or environmental draw? I just can't see a Higher Being intervening in cellular processes. When my rabbi tried to say something about God calling A home for God's own reasons, I asked her not to say that again. Followed by "if God interferes in DNA replication or chromosome segregation, God needs a hobby."

Though this measured and cerebral part is not all of my answer, it is a lot of it. But there is also an incredibly strong emotional part. So strong in fact, that this is one of the extremely few topics associated with bereavement that is guaranteed to raise my blood pressure. (Not in the bereavement police kind of way, where I wish for everyone to share my perception-- I strongly believe in to each her own. But in the don't tell me how to see this kind of way, where I react strongly to anyone implying that the existence of reasons is an undisputed point of agreement among the bereaved, even if one doesn't know what those reasons are in each particular case.)

I could hardly talk to my mother about A's death for months after because she would inevitably end up at "why us?" again. When I finally turned on her to ask why the hell not us, she had nothing coherent. "Because we are such a good close family" is what she came up with. I laughed a long bitter laugh before asking her to please tell me what kind of a family did deserve to have a child die.

When Monkey was born, conceived after more than two years of trying, and after an early miscarriage, I decided that it is impossible to do anything to deserve having a baby. The happiness brought into our lives by finally getting a chance to love and care for and watch grow this tiny being, it was overwhelming. If you asked me then, I probably would've come up with the inverse, that there is nothing (or nearly nothing) one can do to deserve to have their child die. As is, I don't remember actually articulating this last part until after A's death.

Either way, that's where I am-- it's impossible to deserve to have a healthy child, and it's impossible to deserve to have your child die. And, to me, there is no reason. There is no reason good enough for a Higher Being to take your child. And any Higher Being who would disagree is not a Higher Being I want to have anything to do with.

And my final point. Human beings want explanations. And when we don't have them, we make them up. One thing we tend to do a lot is look at a sequence of events, like X happened, and then Y happened, and turn it into X had to happen so that Y could happen, an explanation. And sometimes, if you control for all other moving parts in the system, it is even true. But most of the time it's nothing but a logical fallacy. So I differentiate the things we do after our children die from anything having to do with a reason for why our children had to die. I see what we do after as things we do to learn to live with our tragedies or as we learn to live with our tragedies. Some of these things may be healing, some may be revolutionary and helpful to countless others, and many (most?) are just things we do to get through the days. But to me, none of these things are a good reason. To me, none of them are worth a baby's life.

The way I see it is we move forward because we have to. Putting one foot in front of the other. And sometimes what we do with the shitty hand we are dealt is incredible. Sometimes what we become in the aftermath is stronger and more beautiful than before. But to me, it's not a reason. And not an obligation, either. Just surviving is amazing. Early on, eating and doing laundry, and occasionally showering. Later, engaging in community, real life or virtual, caring about one's job, about politics, books, crafts, anything really. It's all amazing. And, to me, none of it an answer to "why us?"

Do you have bereavement-related topics that get you hot under the collar? For example, how do you feel about the "why us/me?" questions? Are your philosophical or religious answers influenced by your life experiences and perceptions and/or by your professional knowledge?